About Us

THE NEED FOR EFFECTIVE LEADERSHIP IN COMBATING FINANCIAL CRIME IN THE AFRICAN UNION CONTINENTAL FREE TRADE ZONE AREA

Assessing The Impacts of Financial Crime

To

Africa Development Trade Agenda

By Prof. Paul Allieu Kamara

By Prof. Paul Allieu Kamara

Assessing The Impacts of Financial Crime

To

Africa Developments Trade Agenda

FOREWORD

The Need for Effective Leadership is to Promote the fight against Financial Crime in Africa and help to advance Africa Trade Development Agenda

Financial Crime is a major African problem, and combating it requires effective leadership at all levels.

Africa remains at high risk of Financial Crime distress, and the risks have risen in the context of recent large fiscal deficits...

All sectors of African’s Leadership must either act now or never! African Leaders often say that criminal activities are like a lifestyle in the African’s continent: but if left undealt with, the consequences will have adverse effect and will destroy the economic development of Africa and lessen the trust in our Public and Private Institutions. Similarly, leaders must build up effective Political governance within their institutions, the Will and capacity needed to crack down on Financial Crime agents or agencies in the areas of Money Laundering, Counter Terrorism Financing, Fraud, Drug deals, Bribery and Corruption and smugglers, why? Because these criminals have a lot of criminal strategies to evade our African Territories – for example, if they are restricted in the land routes – they would use sea routes- when they are restricted on the seas they use the air. That’s why targeted interventions often have limited impact on Financial Crime and criminal activities in Africa: we need to look at the Leadership capacities and effectiveness in pursing the African Continental Free Trade Zone Area agenda as a big picture, besides the good initiatives and benefits therein it also has negative sides effect of its to tell the whole story of how the criminals are moving on Roads, Seas and air (aviation industry), and the poor border crossing security Agencies of Nations in Africa. This Book intends to tell the story of the poor suffering African’s people with few livelihood options. It is a complex story, with many interconnections; at the heart of which the African Continental Free Trade Zone area lies. While Africa has spread a plethora of beneficial innovations around the world, it has also had many negative consequences in both large and small countries through illicit financial outflows: in fact, security problems in the entire nations of Africa are closely related to the development challenges posed by the Money Laundered to finance Terrorism and Civil Conflicts of Africa. Though the side effects of Financial Crime are particularly strong in the African’s poorest countries those least equipped to respond to these impacts are more vulnerable.

This Book looks at how the role of effective Leadership contributes in the fight beyond specific countries Against Financial Crime and illicit financial flows (fin-iffs) in the African region. The Book zeroed in on Financial Crime, illicit Financial Flows, like Money Laundering, Bribery and Corruption and illicit trade to illustrate the larger scale and the need for effectiveness of African Leaders to combat this menaced: criminal activity is a source of Financial Crime that has a direct relationship to effective Leadership and the dangers it poses for good governance and delivery of social services in Africa. This nexus has received little scholastic attention, yet criminal activity continues to pose negative impact on National development in Africa that hamper effective governance.

Why focus on the Leadership of Africa Continental Free Trade Zone Area?

Several countries in the African continent are suffering from extremely low development indicators because of weak state leaders and their institutions hence the present capacity gaps for developing effective and efficient regulations to combat Financial Crime. As in many developing countries, a large share of uncontrollable economic activity takes place in the informal economy. Not everything informal is bad: in fact, the informal sector often provides precious livelihoods, particularly for the poor. Yet what happens informally happens outside the checks and balances of regulatory systems. As a result, Financial Crime activities like illicit or criminal activities are allowed to flourish more easily, with negative implications for good governance, Educational infrastructure, Health Services, Good Roads, Youth Employment, Agricultural, Peace, stability and development. Under these conditions, resource diversion and other illegal acts that affect a country’s development easily thrive, and damage the integrity of institutions, and distort political governance in ways that disrupt the relationship between citizens and the state thereby put unnecessary pressure on state leaders. Across the region, Financial Crime and illicit financial flows are known to have resourced violent and protracted conflicts due to poor leadership and ineffective monitoring; in the sahel, they resource terrorist groups. Although it is impossible to isolate specific conditions leading directly to criminal activity, structural factors (such as high unemployment and income inequality, exposure to violence, low levels of gross domestic product and weak institutional capacities and ineffective leadership) are known to contribute to a country’s vulnerability. This Book feeds into a strategy of fighting financial Crime and illicit Financial Flows in the African Continental Free Trade Zone Area (AfCFTA,) mandated with the development for co-operation to increase the capacity and effectiveness of African Leaders with issues-based evidence in the area of addressing the risks they pose to National development and insecurity. This strategy started with the publication of Financial Crime advocacy tool for developing countries: measuring the African Continental Free Trade Zone Area responses. Looking at some researched and publications work done, and in the process the Author have discovered that none has written on the Need for Effectiveness of Leadership in Combating Financial Crime and yet the magnitude of the problem remained wider and broader that needs additional research work that begs the need for this Book.

The Effective Leadership is a framework for Africa Continental Free Trade Zone Area member countries to increase their investigations and repatriations of stolen assets to their countries of origin, to do that needs effective leadership driven concept and that is what this new Book is all about, to reduce the negative impact of Financial Crime to National Development in Africa Countries and to focus on preventing Financial Crime and illicit financial flows.

The Book also contributed to a new way of understanding the Impact of Financial Crime and illicit financial flows for National Development as reflected in the 2030 agenda for sustainable development which acknowledges Financial Crime and illicit financial flows as inherently linked to hamper development. The overarching message is timeless: resolving some of the African’s most pressing problems, in this instance Financial Crime and illicit financial flows, requires responding to development challenges, and working in countries at all levels of development to address each part of the spectrum – source, transit and destination. Tackling African challenges requires reforms to happen on all sides.

Usually write about books:

- Our history, what is at stake in the African Continental Free Trade Zone Area? Africa is considered as the second fastest-growing economy after East Asia, and yet the continent is filled with people living in abject poverty and has been referred to as a continent with poor foundations for human development due illicit activities of criminal agencies or persons. Every year, an estimated amount approximated as $88.6 billion, equivalent to 3.7% of Africa's GDP, through Financial Crime and Illicit Capital Flight, (according to UNCTAD Report 2020). Africa is discovered as a net exporter of criminal capital income through Financial Crime which is far more exceeds inflows of assistance, valued at $48bn, and the yearly foreign direct investment, and amounted to $54bn. But It is also discovered that $1.2 trillion and $1.4 trillion has left Africa through Financial Crime between 1980 and 2009—roughly equal to Africa’s current gross domestic product, that surpassing money received from outside over the same period. Financial Crime is said to be dirty money earned illegally and transferred for use elsewhere. Such monies are usually generated from criminal activities, like corruption, tax evasion or tax avoidance, Mis-invoicing, Mispricing, bribes and transactions from cross-border smuggling etc.

The effective of Financial Crime on

sanitation

The effective of Financial Crime on

sanitationThe African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA)designed a flagship project of Agenda 2063 aimed at creating a single African market for goods and services facilitated by free movement of persons, capital, investment to deepen economic integration, promote and attain sustainable and inclusive socio-economic development, gender equality, industrialization, agricultural development, food security, and structural transformation.

The AfCFTA is the world’s largest free trade area bringing together the 55 countries of the African Union (AU) and eight (8) Regional Economic Communities (RECs). The overall mandate of the AfCFTA is to create a single continental market with a population of about 1.3 billion people and a combined GDP of approximately US$ 3.4 trillion.

As part of its mandate, the AfCFTA is to eliminate trade barriers and boost intra-Africa trade. In particular, it is to advance trade in value-added production across all service sectors of the African Economy. The AfCFTA will contribute to establishing regional value chains in Africa, enabling investment and job creation. The practical implementation of the AfCFTA has the potential to foster industrialization, job creation, and investment, thus enhancing the competitiveness of Africa in the medium to long term.

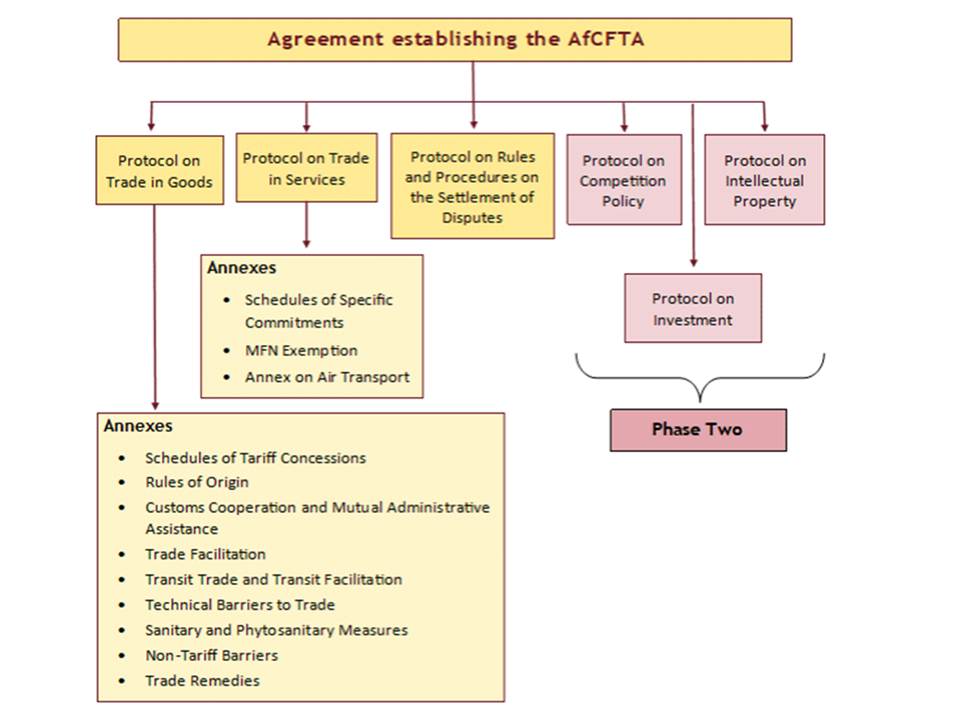

In March 2018, the 10th Extraordinary Session of the African Union Summit held in Kigali, Rwanda, adopted the Agreement Establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). The AfCFTA Agreement came into force in May 2019. As of March 2023, 46 countries had ratified and deposited the instruments of ratifications with the African Union Commission. Mozambique has ratified the Agreement but is yet to deposit the instruments of ratification with the AU Commission. The following countries were yet to ratify the Agreement, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Eritrea, Madagascar, Benin, Liberia, and Libya. Eritrea donot to sign the Agreement of that time.

Trading under the Africa Continental Free Trade Area Agreement began on 1 January 2021. As at February 2022, eight countries representing the five regions of the continent - Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Rwanda, Tanzania and Tunisia – participated in the AfCFTA’s Guided Trade Initiative, which seeks to facilitate trade among interested AfCFTA state parties that have met the minimum requirements for trade, under the Agreement. This initiative supports matchmaking businesses and products for export and import between State Parties. The products earmarked to trade under the Initiative include: ceramic tiles; batteries, tea, coffee, processed meat products, corn starch, sugar, pasta, glucose syrup, dried fruits, and sisal fibre, amongst others, in line with the AfCFTA focus on value chain development.

In the year 2023, the AfCFTA Guided Trade shall also focus on Trade in Services in the five priority areas, i.e. Tourism, transport, Business Services; Communication Services; Financial Services; Transport Services, and Tourism and Travel-related Services. The ultimate objective is to ensure that AfCFTA is truly operational and the gains from the initiative are improved implementation in order to achieve increased inter-regional and intra-Africa trade that would yield economic development for the betterment of the continent at large.

If not curtailed this efforts will soon be hampered by criminal organizations engaging in Financial Crime, the number tells only part of the story. It is a story that exposes how highly complex and deeply entrenched the practices have flourished over the past decades with devastating impact, but barely made it into the news headlines. “The illicit haemorrhage of resources from Africa is about four times Africa’s current external debt,” says a joint report by the African Development Bank (AfDB) and Global Financial Integrity, a US research and advocacy group.

The Financial Crime Problem of Net Resource Transfers from Africa: 1980–2009, found that cumulative illicit outflows from the continent over the 30-years period ranged from $1.2 trillion to $1.4 trillion. The Guardian, a British daily, notes that even these estimates—large as they are—are likely to understate the problem, as they do not capture money lost through drug trafficking and smuggling.

Nonetheless, research and advocacy groups who have worked on Financial Crime or illicit outflows see a direct link between these outflows and Africa’s attempts to mobilize internal resources. Despite annual economic growth averaging 5% over the past decade—boosted in part by improved governance and sound national policies—Africa is still struggling to mobilize domestic resources for investments. If anything, the boost in economic growth has caused a spike in the Financial Crime or illicit outflow.

About three-fifths of global trade is conducted within multinationals.

“Many developing countries have weak or incomplete transfer pricing regimes,” according to the Guardian, citing an issue paper authored by the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a group of high-income economies. The paper says poor countries have weak bargaining power. “Some [countries] have problems in enforcing their transfer pricing regimes due to gaps in the law, weak or no regulations and guidelines for companies,” says the OECD paper, adding that poor countries have limited technical expertise to assess the risks of transfer pricing and to negotiate changes with multinationals.

Offshore tax shelters

According to the OECD paper, member countries are failing to identify company owners who benefit from money laundering. It criticizes OECD members for not doing enough to crack down on Financial Crime or illicit outflows. In order to prevent, uncover or prosecute money laundering, says the paper, authorities must be able to identify company owners. The OECD advises its members to invest in anti-corruption and tax systems in poor countries, as this has high payoffs.

The bulk of Financial Crime dealings or illicit money today is channelled through international tax havens, says the Thabo Mbeki Foundation, an NGO set up by the former president to promote Africa’s renaissance. The foundation accuses “secrecy jurisdictions” of running millions of disguised corporations and shell companies, i.e., companies that exist on paper only. These jurisdictions also operate anonymous trust accounts and fake charitable foundations that specialize in money laundering and trade over-invoicing and underpricing.

“Developing countries lose three times more to tax havens than they receive in aid,” said Melanie Ward, speaking to the Guardian. Ms. Ward is one of the spokespersons for the Enough Food for Everyone IF campaign, a coalition of charities calling for fairer food policies, and head of advocacy at Action-Aid, an anti-poverty group. The money lost, she says, should be spent on essential development of schools, employment, hospitals and roads, and on tackling hunger, not siphoned into the offshore accounts of companies.

A 2007 joint report by the World Bank and UN Office on Drugs and Crime estimated that every $100 million returned to a developing country could fund up to 10 million insecticide-treated bed nets, up to 100 million ACT treatments for malaria, first-line HIV/AIDS treatment for 600,000 people for one year, 250,000 household water connections or 240 km of two-lane paved roads.

Support for new rules to rein in offshore tax shelters has come from an unlikely source—the leaders of eight of the world’s biggest economies, the Group of Eight (G8). Having been stung by the 2008 global financial crisis, the G8 leaders at this year’s summit in Lough Erne, Northern Ireland, introduced—for the first time—rules to fight tax evasion. The rules will now require multinationals to disclose the taxes they pay in countries in which they operate.

During the run-up to the G8 summit, advocacy groups campaigned to get rich countries to introduce laws on transparency in corporate taxes. Among them was the Africa Progress Panel, chaired by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan. On the eve of the summit, it published its annual flagship report, Africa Progress Report 2013, strongly criticizing the current rules on corporate transparency.

Unconscionable act

“It is unconscionable that some companies, often supported by dishonest officials, are using unethical tax avoidance, transfer pricing and anonymous company ownership to maximize their profits while millions of Africans go without adequate nutrition, health and education,” Mr. Annan wrote in the foreword to the report. Tax evasion, he said, has cut into African citizens’ fair share of profits from their abundant resources.

In the end, the G8 leaders adopted the Lough Erne Declaration, a 10-point statement calling for an overhaul of corporate transparency rules. Among other things, the declaration urges authorities to automatically share tax information with other countries to fight tax evasion. It states that poor countries should have the information and capacity to collect the taxes owed to them. The declaration further calls on extractive companies to report payments to all governments, which should in turn publish them.

While the Financial Times embraced the declaration as “an advance” in corporate transparency, Sally Copley, another spokesperson for the IF campaign, says in a statement, “The public argument for a crackdown on tax dodging has been won, but the political battle remains.” Copley wants the G8 to impose strict laws on tax evasion.

For its part, Africa Progress Report 2013 calls for multilateral solutions to global problems because “tax evasion, Financial Crime and illicit transfers of wealth and unfair pricing practices are sustained through global trading and financial systems.” It urges African citizens to demand the highest standards of propriety and disclosure from their governments, and rich countries to demand the same standards from their companies.

Initiatives by institutions in Africa and the adoption of the Lough Erne Declaration raise hopes for strict rules against Financial Crime and illicit financial flows from Africa. “Seizing these opportunities will be difficult. Squandering them would be unforgivable and indefensible,” Mr. Annan warns in his foreword to the panel’s report. Meanwhile, ECA’s slogan “Track it. Stop it. Get it” aptly captures what needs to be done about Financial Crime and money flowing illicitly out of Africa.

“The traditional thinking has always been that the West is pouring money into Africa through foreign aid and other private-sector flows, without receiving much in return,” said Raymond Baker, president of Global Financial Integrity, in a statement released at the launch of the report earlier this year. Mr. Baker said the report turns that logic upside down, adding that Africa has been a net creditor to the rest of the world for decades.

The composition of these outflows also challenges the traditional thinking about Financial Crime and illicit money. According to estimates by Global Financial Integrity, corrupt activities such as bribery and embezzlement constitute only about 3% of Financial Crime and illicit outflows criminal activities such as drug trafficking and smuggling make up 30% to 35% and commercial transactions by multinational companies make up a whopping 60% to 65%. Contrary to popular belief, argues Professor Baker, money stolen by corrupt governments is insignificant compared to the other forms of Financial Crime and illicit outflow. The most common way Financial Crime or illicit money is moved across borders is through international trade.

Information scanty and scattered

A ten-member high-level panel chaired by former South African President Thabo Mbeki leads research by the UN Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) into Financial Crime or illicit financial flows, assisted by ECA Executive Secretary Carlos Lopes as the vice-chair. Other members of the panel include Professor Baker and Ambassador Segun Apata of Nigeria. The ECA blames Financial Crime and illicit outflows for reducing Africa’s tax revenues, undermining trade and investment and worsening poverty. Its report was released in March 2014.

Undoubtedly the panel faces a daunting task. Charles Goredema, a senior researcher at the South Africa–based Institute of Security Studies, cautions the panel on the challenges ahead. Writing in the institute’s newsletter, ISS Today, Goredema warns the panel that it will find that in many African countries, data on Financial Crime and illicit financial flows “is scanty, clouded in a mixed mass of information and scattered in disparate locations.” He ranks tax collection agencies and mining departments among the bodies most reluctant to share data.

Goredema lists Transparency International, Global Financial Integrity, Christian Aid and the Tax Justice Network as some of the advocacy groups that have tried to quantify the scale of Financial Crime and illicit financial flows. The extent of such outflows remains a matter of speculation, he says, with the figures on Africa ranging between $50 billion and $80 billion per year. Other estimates by the ECA put the figure at more than $800 billion between 1970 and 2008.

“The absence of unanimity on [the amount] is probably attributable to the fact that the terrain concerned is quite broad, and each organization can only be exposed to a part of it at any given point in time,” Goredema writes, adding, “It is less important to achieve consensus on scale than it is to achieve it on the measures to be taken to stem illicit financial outflows from Africa.”

Financial crime linked to Nigeria

Financial crime linked to Nigeria is a large and pressing problem for the British authorities, which are short of the information and resources needed to deal with it. Nigeria-related financial crime has grown in significance partly because it is not seen as a priority area. Private sector fraudsters and corrupt public officials and British companies have profited from the general Western focus on terrorist financing, drugs and people-trafficking. Other types of corruption and money-laundering, some of which involve British business people, have often been neglected. These general observations could be applied to crimes carried out by the nationals of many countries, including Britain itself. Criminal activity involves only a small minority of Nigerians, relative to the size of the country and the number of its national’s resident in Britain or visiting it. Nigeria is Africa’s most populous nation by far and is a former British colony: Jack Straw, the former foreign secretary, has referred to estimates that more than one million Nigerians live in Britain. 1 it is precisely because of these strong and deep links that Nigeria-related financial crime deserves attention. High levels of such crime are very damaging to the image and standing of the many Nigerians who live honestly in Britain or who visit the country to do legitimate business. One Lagos banker has described how the level of crime linked to Nigeria already leads holders of the country’s distinctive green passport to be ‘victimized’ anywhere they go in the world. Equally, the proportionally small but still substantial numbers of Nigerians who are involved in financial crime create a risk of what Tarique Ghaffur, a Metropolitan Police assistant commissioner, has described as large-scale ‘contamination of communities’ by organized crime.2 Extensive anecdotal evidence suggests that a significant amount of financial crime in Britain is linked to Nigeria. One police officer working on economic and specialist crime says so much Nigeria-related corruption goes through London that he could employ his entire command to deal with it. Another, who works on Cheque and credit card fraud, says Nigerians are in the ‘top three’ of nationalities of offenders with whom his group has to deal.3 The piecemeal figures on Nigeria-related fraud that do emerge seem at times to echo the recent warning of Bob Murrill, head of the Metropolitan Police organized crime unit, that criminal gangs are ‘out of control’ in London.4 On a single day check at Heathrow airport last year, for example, police discovered more than £20 million of forged cheques and postal orders in the courier mail from Lagos. Recent British government research found that at least 13 per cent of Nigerian applicants for visitors’ visas and at least 17 per cent of applicants for student visas tried to use some kind of fraudulent documentation, such as forged bank statements or tax returns.5 Many informed people think a large amount of Nigerian official corruption passes through Britain. In 2005, the British authorities charged D.S.P. Alamieyeseigha, governor of Nigeria’s Bayelsa state, with money-laundering after almost £1 million in cash was discovered at one of his London properties. A Nigerian law enforcement official estimates that between 80 and 90 per cent of the country’s 36 state governors own property in Britain, with many also having bank accounts in their own, their wives’ or their children’s names. Other important components of Nigeria-related financial crime are the British individuals and companies operating corruptly in Nigeria. London is increasingly attacked for alleged hypocrisy in failing to keep its promises to crack down on British corruption in Africa. Privately, British business people admit corruption is still commonplace: one British executive working in the oil industry says his company routinely pays immigration officials a bribe worth between 20 and 30 per cent of the cost of expatriate resident permits. In March 2006, a report by Britain’s All Party Parliamentary Group on Africa criticized the ‘limbo like state of anti-corruption legislation’, and the ‘fragmentation and under-resourcing’ of investigatory and enforcing agencies.6 The accusations come more than five years after Britain revealed that at least $1.3 billion looted by the late dictator General Sani Abacha had been processed through British financial institutions.7 Nigerians responsible for investigating financial crime in Nigeria have had some successes, but many are under no illusions about how severe and deeply entrenched the problem is after decades of autocratic government, rampant corruption and plunging living standards. Nigeria’s Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) estimates that in under four years of operation it has recovered £2 billion of criminal money.8 One of its officials laments that Nigerian internet fraud has become ‘something huge’ because the authorities never seriously tried to stop it until very recently. The same could happen in Britain, he warns, if it makes the same mistake.

Corruption is endemic in Sierra Leone.

Sierra Leone is widely considered to be one of the most politically and economically corrupt nations in the world and international rankings reflect this. Transparency International's 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index scored Sierra Leone at 34 on a scale from 0 ("highly corrupt") to 100 ("very clean"). When ranked by score, Sierra Leone ranked 110th among the 180 countries in the Index, where the country ranked first is perceived to have the most honest public sector.[1] For comparison, the best score was 90 (ranked 1), the worst score was 12 (ranked 180), and the average score was 43.[2] The 2018 Global Competitiveness Report ranked Sierra Leone 109th out of 140 countries for Incidence of Corruption, with country 140 having the highest incidence of corruption.[3] Corruption is prevalent in many aspects of society in Sierra Leone, especially in the aftermath of the Sierra Leone Civil War. The illicit trade in conflict diamonds funded the rebel Revolutionary United Front (RUF) forces during the civil war, leading to fighting between the Sierra Leone Army and the RUF for control of the diamond mines.[4] Widespread corruption in the health care sector has limited access to medical care, with health care workers often dependent on receiving bribes to supplement their low pay.[5]

In understanding the problems of corruption in African Union Member States we can seek to solve the current issues in Africa.

Income inequality is rising, while underemployment and the lack of economic opportunities push some individuals to join criminal groups, gangs or rebel movements, reinforcing the links between inequality, criminal activity and violence. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa’s High Level Panel on Financial Crime and Illicit Financial Flows has estimated that illicit financial flows (IFFs) from Africa could amount to as much as USD 50 billion (US dollars) per year. Although the figures on IFFs are heavily disputed, current analyses agree that IFFs exceed the amount of Official Development Assistance (ODA) provided to Africa. Previous research has largely focused on capturing the volumes and sources of Fin-Crime and IFFs, and on identifying the commercial practices that contribute to them such as trade misinvoicing, mispricing, tax evasion and avoidance, and transfer pricing. This Book takes a different approach by seeking to build the evidence basis on criminal and illicit economies, the Fin-Crime and IFFs these economies generate, and their impact on development. The Book reviews diverse forms of economies prevalent in Africa that are usually seen as criminal or illicit, organizing them through a typology according to a range of illegal activities, from natural resource crimes to illicit trade in normal legal goods. This analysis leads to the following conclusions: Financial Crime, criminal and illicit economies produce IFFs that undermine country capacities to finance their development; and criminal economies and IFFs are a potent negative force that contribute to the degradation of livelihoods and ecosystems, undermine institutions, reinforce clientelist politics and enable impunity, in different ways across the region’s countries. Key findings Criminal acts are enabled by a diverse set of actors, including criminal networks, the private sector (both domestic and international), and state officials. Criminal methods are dynamic processes, changing in response to opportunities, and to global and local market forces. IFFs and Financial criminality erode the fabric of the state across the region, and often cause politics, business and crime to converge, creating ambiguity around governance and rule of law. Certain criminal and illicit economies in the region carry low levels of stigma within communities, as they are an important source of livelihood, building legitimacy that enables alternative governance providers to compete with the state and create alternate sources of authority.

- achievements,

-

OVERVIEW AND DEFINITIONS

What are some of the main reasons for fighting Financial Crime in the African Continental Free Trade Zone Area?

Interferes with government revenue:

1. To protect the Resources: As part of protecting the resources of Africa, financial criminals will often try to avoid paying taxes on goods and services. This gives a country's government less money to spend on important projects, makes tax collection more difficult, and often results in higher taxation on legitimate citizens.

2. Some people and groups will do anything for money or other forms of wealth—even resort to breaking the law. They may try to claim that these financial crimes are justifiable because they have no victims, or that the victims can afford the losses. In reality, they are still illegal because they can cause widespread harm—not only in finance, but also in business, politics, and culture.

So what are financial crimes, and what are some common types? Why are they so damaging to so many areas of society?

And what can organizations expect the battle against financial crime to look like in the near future? We’ll cover all that and more in this Book.

In other to walk through this Book we have to understand the main definitions and terms that defines this Book.

Let us look at some Terms and definitions according to the Oxford Languages Dictionary.

African Union Continental Free Trade Zone

What is Africa Continent?

Africa is a Continent: The most important thing to know is that Africa is not a country; it's a continent of 55 countries that are diverse with culturally and geographically different. It's so diverse because Africa is really big as big as the combined landmasses of China, the United States, India, Japan and much of Europe.

What is Union?

· A union is a state of being united, a combination, as the result of joining two or more things into one: to promote the union between two families; the Union of African brings all Countries of Africans into one Union-Called the African Union (AU).

· A union is a workers' organization which represents its members and which aims to improve things such as their working conditions and pay.

What is a Continent?

What is a simple definition of continent?

A continent is a large continuous mass of land conventionally regarded as a collective region. There are seven continents: Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe, and Australia (listed from largest to smallest in size)

What is Free?

1. Able to act or be done as one wishes; not under the control of another

· Not or no longer confined or imprisoned.

· Without cost or payment.

· Release from confinement or slavery.

· Remove something undesirable or restrictive from

2. What is Trade?

The action of buying and selling goods and services

Commerce:

· buying and selling

· dealing with traffic or transporting of business

· marketing and merchandising

· bargaining and dealings

· transactions and negotiations

· proceedings

3. A job requiring manual skills and special training. "The fundamentals of the construction trade"

Similar:

· craft occupation

· job day job

· career

· profession

· business

· pursuit living

· livelihood

· line of work

· line of business

· vocation calling

· walk of life province

· field work

· employment

4. What is Zone?

· An area, especially one that is different from the areas around it, because it has different characteristics or is used for different purposes: a danger/safety zone.

· an area or stretch of land having a particular characteristic, purpose, or use, or subject to particular restrictions

· An encircling band or stripe of distinctive colour, texture, or character.

5. What is Area?

Area is defined as the total space taken up by a flat (2-D) surface or shape of an object. The space enclosed by the boundary of a plane figure is called its area. The area of a figure is the number of unit squares that cover the surface of a closed figure.

What is Financial Crime?

Financial crime is any activity that allows an individual or group to unlawfully gain financial assets (including money, securities, or other property). It typically involves directly stealing from a person or institution, or else illegally changing or obscuring who owns an asset.

Financial crime is sometimes referred to as “white-collar crime” because it targets assets rather than people themselves, and so tends to be non-violent (but not always). In any event, it can still be extremely damaging to individuals’ financial situations, and even regional or global markets.

What are the types considered a Financial Crime?

Financial crimes can be divided into two categories.

· The first category is an entity generating financial benefits for themselves or others through deceptive or illicit practices. This can include a business employee using privileged information to misappropriate some of the company’s or state funds for their own use. Another example would be criminal taking money or other assets from someone in exchange for a financial instrument (such as a Cheque or Money order) that turns out to be fake

· The second category is an entity committing a crime that sets them up to commit another crime where they illegitimately gain a financial advantage or protect their financial benefits through dishonest or illegal methods. The most recognizable form of the latter is money laundering: putting the proceeds of crime through a series of complex transactions to make them appear as if they came from a legitimate source. Another example is people using shell corporations or shell banks to store their money, obscuring who owns it and therefore helping them avoid paying taxes on it.

What is a Shell Corporation?

A shell Corporation is an entity with no active business operations or assets. These firms are often set up for illegal activities, such as tax evasion and money laundering, and to maintain anonymity during transactions. What are the Problems of shell corporation?

Some of problems of Shell Corporations

Shell corps has minimal operations and exists only on paper, with a registered office and nominal directors/shareholders. They can be established quickly in jurisdictions with favorable regulations for company formation and privacy.

The primary use of a shell crop is for illegal activities while appearing legitimate. For example, individuals or organizations may hide assets and launder money by transferring funds through multiple shell corps. Due to the complex ownership and operations across multiple jurisdictions, it is difficult to trace those behind these activities.

To prevent abuse, governments should implement measures such as stricter regulatory requirements, enhanced due diligence, and increased transparency. These efforts aim to prevent criminals from exploiting shell corps for illegal purposes.

Legitimate firms can also utilize shell corps, such as multinationals creating subsidiaries in different countries for tax planning or to simplify corporate structures. In these cases, the primary purpose is not illegal activities but to facilitate legitimate business operations.

To ensure that shell corps, are not misused, regulations should include Know Your Customer (KYC) procedures when registering new companies. This involves conducting comprehensive background checks on directors and beneficial owners to verify their identities and credibility.

Authorities should also require more reporting on financial transactions and beneficial ownership structures. By collecting and sharing this information internationally, law enforcement agencies can better detect and investigate activities involving shell corps.

Other Shell Corporations Definitions

Shell corporations, or shell entities, are defined by their lack of substantial business operations or assets. They are inactive and used for various financial transactions. Legitimate uses of shell corporations include tax planning, asset protection, and confidentiality. But, they can also be used for illicit activities like money laundering and fraud.

Characteristics of Shell Corporations:

1) Shell corporations usually have no physical presence or employees. They may have a registered address, but no actual office or staff. This makes it hard to trace the true owners.

2) Nominee directors and shareholders are often used. These people act on behalf of the owners, but their names are listed in public records. This allows for anonymity.

3) Shell corporations usually have minimal capitalization and nominal assets. They may only hold a small amount of cash or shares in other companies. This makes it difficult for authorities to seize assets or hold the entity accountable.

4) Complex financial transactions are often carried out by shell corporations. These transactions are done to hide funds, evade taxes, or disguise illegal activities. This further complicates investigations.

The Guardian found that, between 1995 and 2015, over 175,000 shell companies were set up in London with ties to offshore tax havens, such as British Virgin Islands and Panama Papers leak sources.

Legal and Ethical Issues Surrounding Shell Corporations

· Embezzlement Controls

· Cybercrimes embezzlement schemes

Shell corporations can bring a lot of legal and ethical problems. They’re often used for bad stuff, like money laundering, embezzlement, and dodging taxes. Here’s a breakdown of the main issues:

Money Laundering: People use shell corporations as a way to funnel illegal money.

Tax Evasion: By using overseas shell corporations, people can dodge taxes in their own countries.

Fraud: Shell corporations are sometimes set up for fraud, like Ponzi or pyramid schemes.

Anonymous Ownership: People use shell corporations to hide their identity, making them hard to punish for bad behavior.

Regulatory Compliance: Shell corporations can manipulate regulations and get away with it.

These aren’t the only problems with shell corporations. Terrorism financing and corruption are also involved. To crack down on them, regulatory bodies all over the world are keeping an eye out.

Tip: When dealing with others, check if they have any links to shell corporations to avoid the risks.

Types of Financial Crime

Financial crime has a broad definition that sometimes includes all illegal activity targeting financial institutions, or even any illicit generation or use of money for an advantage. Here are ten common types of financial crime.

Fraud

Financial fraud crimes encompass any activities intended to gain or protect financial benefits through deceitful and unethical means. Fraud is a wide category that can include many of the other crimes on this list, such as impersonation, counterfeiting, identity theft, and falsifying business records.

Money Laundering

Money laundering is a financial crime that aims to cover up the source of the proceeds of crime. Its first objective is to sneak money generated through illegal activities into a financial system (placement). Its second objective is to move that money around to build up a transaction history, giving it the appearance of legitimacy and making it difficult to trace back to its original criminal source (layering/structuring). Its final objective is to return the money to criminals for them to spend without attracting attention from authorities (integration).

Terrorist Financing

Terrorist financing refers to entities providing financial assets to terrorists—both individuals and groups. Their aim is to help terrorists purchase weapons, supplies, and anything else they need to carry out attacks on innocent civilians.

The penalties for being caught aiding terrorists are very severe, so terrorist financing is somewhat akin to money laundering. That is, criminals wanting to finance terrorists have to use tricks to sneak assets into legitimate financial systems, then conceal where the money is coming from and going to.

Embezzlement

Embezzlement is when an entity is entrusted with—or given access to—funds to be used towards certain ends, with the entity then illicitly using that money for other purposes. They may transfer it to their own accounts or those of another, creating fake invoices or receipts to try and cover their tracks. Embezzlement often occurs within organizations and can range from petty theft to multi-million dollar schemes.

Corruption and Bribery

Similar to embezzlement, corruption is when an entity in a position of power acts outside of its mandate in order to unlawfully gain advantages—including financial ones—for themselves or others. Corruption can actually involve embezzlement, and it can also involve bribery.

Bribery is the other side of corruption. It’s when an entity illegally gives financial benefits to authorities in exchange for receiving preferential treatment in decisions affecting the public. An example is a company paying officials in a country to get them to allow it to operate there without needing to comply with all necessary regulatory obligations.

Tax Evasion

An entity intentionally not paying their taxes, or paying less tax than they owe, is a financial crime called tax evasion. There are several ways to commit tax evasion. One is to deliberately fail to report taxable income. Another is to purposely claim more tax deductions than one is entitled to. Refusing to file a tax return at all also counts as tax evasion.

An entity may also commit tax evasion by storing or investing their assets in banks or companies in other countries, or that are “shells” (i.e. they have no physical location and/or no active operations). This allows them to falsely claim that they have fewer assets than they actually do, in an attempt to illegally pay less tax than they truly owe.

Insider Trading and Market Abuse

Sometimes, an entity may cheat the stock market by buying or selling securities based on proprietary information regarding a company’s financial situation. This is called insider trading, and it’s a financial crime in many places. This is because the entity either was entrusted with the information for other purposes (similar to corruption and embezzlement) or outright stole it. So they got an unfair advantage by using information the public wasn't supposed to know (yet).

There are other ways criminals can illegally manipulate stock markets. One example is “wash trading”—purchasing and then immediately re-selling shares in a company. This creates the illusion that the company’s stock is seeing a lot of financial activity, which can inflate its price.

Another such scheme is called “pump and dump”. This involves an entity purchasing a low-value stock, then spreading rumors or other misinformation suggesting that the stock will soon increase in price. Their goal is to create a flurry of trading activity around the stock, thereby inflating its value. Then they sell off their shares for a profit before others realize the hype surrounding the stock was fake, and trading activity returns to normal.

Forgery and Counterfeiting

Other financial crimes involve unlawfully manipulating or duplicating financial assets. These are known, respectively, as forgery and counterfeiting.

Forgery is illicitly altering a genuine financial asset to create an unintended benefit. In check fraud, for example, a criminal may name a different payee on the check, or change the amount the check is for. They may even attempt to fake the signature or other credentials of the check payer or endorser to make it seem like they authorized the check, when in fact, they did not.

Meanwhile, counterfeiting creates imitations or unauthorized copies of legitimate financial assets. The criminal’s intention is to spend these fakes as if they were genuine, hoping the other transaction party doesn’t notice the difference. However, many financial assets now have security features that allow people to tell the difference between an imitation and a genuine one, or when a genuine one has been illegally copied.

Identity Theft

While identity theft doesn’t involve directly stealing financial assets, it’s often considered a financial crime anyway. This is because it’s typically used as a means of committing other financial crimes.

The goal is for a criminal to steal someone’s private identity or account access credentials, then use them to forge the person’s authorization for transactions. This allows the criminal to illegally profit while the victim bears the costs.

A criminal can use many different methods for identity theft. A common one is phishing, where they trick victims into revealing their credentials with an enticing and/or urgent request—often appearing as if it came from a legitimate and authoritative source. They can also break into online accounts to steal credentials or impersonate victims. Or they may simply purchase credentials exposed by data breaches from the black market.

Cybercrime

As more financial activity moves online, so too does financial crime. Fraudsters are turning to digital channels for stealing money and authorization credentials, exposing sensitive information, forging and counterfeiting financial assets, manipulating markets, and committing many different types of fraud.

Virtual currencies are proving to be especially popular tools for financial crime. Reasons for this include a current lack of financial regulations surrounding them, as well as most transactions being semi-anonymous. In addition, many virtual currencies have non-centralized administration on the block-chain, making transactions difficult to undo once recorded.

All of this has made virtual currencies ripe for schemes such as market manipulation, money laundering, terrorist financing, tax evasion, and other forms of fraud.

• Market Abuse and Insider Dealing:

Market abuse and insider dealing involve using inside information to make financial gains or manipulate markets. This can include insider trading, spreading false rumors, or manipulating stock prices.

• Information Security:

Information security involves protecting sensitive information from unauthorized access or disclosure. This can include theft of personal information, hacking into computer systems, or corporate espionage.

Financial Crime Statistics and Trends to Watch For

According to the Price Water house Coopers 2022 Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey, about 46% of organizations worldwide encountered some kind of financial crime that year. Financial crime is tending to target larger organizations—52% of those targeted in 2022 had annual revenues over $10 billion US, as opposed to 38% of companies with less than $100 million US annual revenue.

And financial crime is becoming more costly, more often. Of larger companies experiencing fraud, 18% had their biggest incident of financial crime in 2022, costing them over $50 million US. And 22% of smaller companies experiencing fraud said their most disruptive financial crime experience cost them at least $1 million US.

Here are some other financial crime trends to watch for in the coming years.

The rise of financial crime in cyberspace

While global financial crime statistics show an overall downward trend, one notable exception is in cybercrime. The COVID-19 pandemic fueled the demand and adoption of instantaneous remote financial services, including neo-banks, virtual currency trading, and embedded finance.

However, these services tend to prioritize smooth user onboarding and interface experiences at the expense of more robust security and risk assessment programs. This leaves them more vulnerable to bad actors—especially hackers, online fraudsters, and other external parties.

A renewed importance for sanctions screening

Incidents such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February of 2022 have put a spotlight back on sanctions list compliance. Organizations are scrambling to avoid being penalized for illegally dealing with dangerous individuals, groups, and countries—both directly and throughout their supply chains. This will be made more difficult by the increasing popularity of decentralized financing, such as through virtual currencies and crowd funding.

AI and other changing financial crime prevention procedures

Regulators and compliance teams continue to realize that if they want to keep up with modern financial crime, they need to do things differently. That includes adopting machine learning models to more accurately identify signs of financial crime, as well as prioritize the alerts most likely to be true positives.

It also includes taking a more holistic, organization-wide approach to fighting financial crime. That involves stronger communication between departments to assess customer risk across both onboarding and ongoing financial activity. It also involves more stringent auditing processes to ensure all parts of an organization are on board with its overall compliance efforts.

Consequences of Money Laundering and Financial Crime

Again, while financial crime is typically non-violent, it can be used to cover up violent crimes that involve criminals taking what doesn’t rightfully belong to them. Beyond that, financial crime can have far-reaching socio-economic impacts that can threaten the administrative stability of entire countries, and even the world.

Here are some reasons why.

· Unfairly disadvantages legitimate private businesses: Individuals and groups that engage in financial crime sometimes conceal their activities behind “front” businesses. Since these businesses are backed by substantial amounts of illegal money, they can often offer their products or services at costs that legitimate businesses just can’t match.

· Warps industry supply and demand: Financial criminals invest in crime to profit. So when they do invest in legitimate industries, it’s often as a means of protecting their assets through money laundering and not because they expect returns. This false demand can put industries in danger of collapsing when criminals decide to move their money somewhere else.

· Threatens the stability of financial institutions: Financial institutions that house the proceeds of financial crime tend to see large amounts of money move around quickly. This is usually either to launder the funds or to keep them away from investigating authorities. That can cause liquidity problems for the FI, which in turn can cause customers to panic and go on bank runs.

· Interferes with government revenue: As part of protecting their proceeds, financial criminals will often try to avoid paying tax on them. This gives a country’s government less money to spend on important projects, makes tax collection more difficult, and often results in higher taxation on legitimate citizens.

· Hampers the economic growth of developing countries: Countries emerging as players on the world economic stage tend to be focused on growing their financial systems as opposed to regulating them. This makes them attractive to financial criminals, which makes them less attractive to people and companies looking to legitimately do business.

· Hijacks control of economic policy: Another danger of financial crime being popular in lightly-regulated developing countries is that its proceeds may exceed the budgets of governments in those countries. This effectively means that criminals are in control of the country’s economy instead of the legitimate government.

· Contributes to moral breakdown: If financial crime is left unchecked in a country, it encourages more people to become involved. This results in more victims of criminal activities—such as drug distribution and human trafficking—who may eventually turn to crime themselves out of isolation and desperation. This cycle can subvert a country’s rule of law, and even its democratic principles.

Examples of Financial Crime

To illustrate what financial crime looks like in real life, here are a few famous examples of financial crimes that received significant media attention.

Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi Scheme

Bernie Madoff founded a legitimate investment firm in the 1960s, but it eventually morphed into the biggest Ponzi scheme in history. It took money from investors and used the funds to pay out dividends to clients who had come earlier; instead of to back what customers actually wanted to invest in. The fraud, worth $65 billion, was publicly exposed in 2009. Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in prison, and died in 2021.

Enron’s Accounting Fraud

At the turn of the 21st century, the American energy company appeared to be one of the most profitable corporations in the world. The reality, however, was that the business was deeply in debt. The company’s executives—along with accounting firm Arthur Andersen—had been hiding Enron’s money woes behind misleading financial reporting, accounting loopholes, and off-books subsidiary shell corporations.

By late 2001, investors and journalists had exposed Enron’s fraud, putting the business on the verge of bankruptcy. The company’s collapse cost investors upwards of $74 billion US, and several executives from both Enron and Arthur Andersen were sentenced to long prison terms. The scandal led the US government to pass the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002 to impose stricter regulations on corporate financial reporting.

Martha Stewart’s ImClone Insider Trading Scandal

The famed retail entrepreneur, author, and TV personality was involved in a very public insider trading scandal in the early 2000s. Her former stockbroker, Peter Bacanovic, illegally told her that ImClone—a biotechnology company she had shares in—was about to have an experimental cancer treatment rejected by the Food and Drug Administration. Knowing this would drive down the company’s stock price, Stewart sold her shares a day before the announcement went public.

The Securities and Exchange Commission launched an investigation, refusing to believe this move was mere coincidence. In mid-2003, both Stewart and Bacanovic were charged with insider trading. Stewart was found guilty and served 5 months in prison.

Financial Crime Prevention: How Governments and Businesses Can Stop Financial Crime

Today, many criminals who commit financial fraud, launder money, and engage in terrorist financing are incredibly sophisticated and agile, allowing them to continue their criminal activity without detection.

For businesses to avoid exposure to these sorts of illegal actions, they must take preemptive actions, including investing in the infrastructure and systems needed to prevent and identify any kind of criminal activity.

Many of these financial crimes require cross-border transactions. Unfortunately, the current international financial network makes sophisticated criminal activity even more challenging to trace and prosecute. Money launderers leverage differences in regulations to move money between countries, clouding the trail.

And those financing terrorist activities need to transfer money in and out of countries to execute their attacks. To complicate matters further, in-country connections such as government officials, bank employees, accountants, and others make it easier for these illegal cross-border transactions to go undetected.

Most countries have deployed comprehensive regulations to enable financial institutions to help detect, investigate, and report suspicious activity.

Banks and financial institutions must comply with the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) in the US. In addition, the UK has instituted the Proceeds of Crime Act (POCA), while the EU has put in place the Anti-Money Laundering Directives (AMLD). All of these regulations are consistent with the guidance provided by the intergovernmental organization, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

By complying with these regulations, financial institutions can help prevent financial crimes such as fraud, money laundering, and the financing of terrorist activity. On top of this, teams can optimize operations and reduce false positives. Compliance generally falls into detecting suspicious activity, investigation, and reporting to the appropriate government entity.

Unit21’s Anti-Fraud and AML Infrastructure is Here to Help You Guard Against Financial Crime

There’s no denying that it takes a lot of work to stop financial crime. Compliance with national and international detection and prevention standards is a good start. However, this is often easier said than done. New types of financial crimes are constantly appearing as policies, procedures, and technologies change. So regulations—and, consequently, organizations’ compliance programs—have to adapt as well.

Ultimately, countering financial crime is about risk management: knowing how and where an organization is vulnerable, and implementing the proper controls where reasonable—including identity verification, transaction monitoring, and case management. This helps the organization not only limit the chance of being victimized by financial crime but also work quickly to control the damage financial crime causes if it actually happens.

Of course, using digital tools like Unit21’s is much more efficient than trying to handle everything manually. Contact us for a demo of how our infrastructure can save an organization time, money, and other resources.

What is African Union Continental Free Trade Zone is all about?

· What is the AfCFTA?

AfCFTA by simply definition can be described as an interest ground that came together to defend the continental resources and trade right. The AfCFTA is composed of almost all African countries. With Nigeria and Benin having agreed to join in, only Eritrea is yet to sign. Eritrea’s government declared that they will most likely come on board. This would result in a continental trade agreement and the largest FTA.

The AfCFTA is an ambitious trade pact to form the world’s largest free trade area by creating a single market for goods and services of almost 1.3bn people across Africa and deepening the economic integration of Africa. The trade area could have a combined gross domestic product of around $3.4 trillion, but achieving its full potential depends on significant policy reforms and trade facilitation measures across African signatory nations.

The AfCFTA aims to reduce tariffs among members and covers policy areas such as trade facilitation and services, as well as regulatory measures such as sanitary standards and technical barriers to trade.

The agreement was brokered by the African Union (AU) and was signed by 44 of its 55 member states in Kigali, Rwanda on March 21, 2018. The only country still not to sign the agreement is Eritrea, which has a largely closed economy.

As of May 2022, 46 of the 54 signatories had deposited their instruments of ratification with the chair of the African Union Commission, making them state parties to the agreement.

Figure 1.1 Leadership and Trade-nexus

The AfCFTA Secretariat, an autonomous body within the African Union based in Accra, Ghana, and led by secretary general Wamkele Mene, is responsible for coordinating the implementation of the agreement. (1. https://african.business/2022/05/trade-investment/what-you-need-to-know-about-the-african-continental-free-trade area#:~:text=The%20AfCFTA%20is%20an%20ambitious,the%

Objective:

The main objectives of the ACFTA are to create a single continental market for goods and services, with free movement of business persons and investments, and thus pave the way for accelerating the establishment of the Customs Union.

Why is this Book looking at Financial Crime, criminal economies and illicit financial flows in Africa?

Financial crimes can have serious consequences or impacts for the African Union Leaders, individuals and society as a whole, including economic instability, loss of public trust in financial institutions, and erosion of the rule of law.

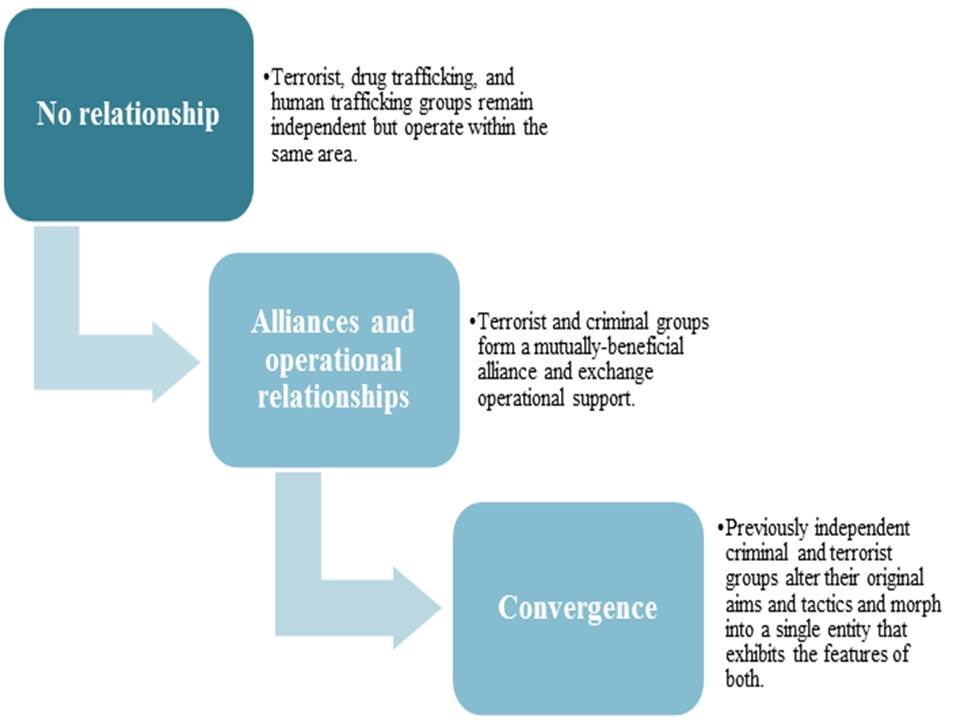

Organized criminal groups, however, may also adopt terrorist tactics of indiscriminate violence and large-scale public intimidation to further criminal objectives or fulfill special operational aims. Organized criminal groups and terrorist organizations may build alliances with each other. The nature of these alliances varies broadly and can include one-off, short-term, and long-term relationships. With time, criminal and terrorist groups may develop a capacity to engage in both Financial Crime and Illicit Financial outflows into their criminal and terrorist activities, thus forming entities that display the characteristics of both groups.

Financial crime is a broad term used to describe criminal activities that involve money or other financial resources. It refers to any illegal activity that involves the use of financial systems, institutions, or instruments for illicit purposes, typically with the goal of generating profits for the perpetrators.

Financial crimes can take many different forms:

1. Money laundering

2. Fraud,

3. Embezzlement,

4. Insider trading or Fraud

5. Cybercrime.

6. Bribery and Corruption

Who Commit these Crimes?

These crimes are often committed by:

· Individuals

· groups of People

· Governmental and Non-Governmental Organizational

· Banking and other Financial Institutions Seeking to profit

From illegal activities,

Ø Such as drug trafficking,

Ø Human trafficking, or

Ø Terrorism.

Ø Rebel Wars

Figure 1.2 Crime-terror nexus

Financial crime is a complex and ever-evolving problem that requires a multifaceted approach to combat. This includes all Leadership sector, the Law enforcement agencies, regulatory bodies, and financial institutions all play important roles in detecting and preventing financial crimes. Leaders should implement Effective measures to combat financial crime include strengthening anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing regulations, enhancing cross-border cooperation, and leveraging technology and data analytics to identify suspicious activities.

Financial Crimes are criminal activities carried out by individuals or criminal organizations to provide economic benefits through illegal methods. Financial crimes, which have become a critical issue in recent years worldwide, cause significant harm to the economy and society of Africa. Income from financial crimes corresponds to a substantial proportion of global GDP. Therefore, regulatory bodies constantly develop new tactics to combat financial crimes. In addition, with the development of technology, criminals develop new tactics. Today's most common financial crimes are terrorist financing, money laundering, corruption, and fraud.

Money laundering is the process of turning earnings from crime into legal earnings. Cartels and gangs are the most common money launderers. Some sophisticated techniques may include different financial institutions such as accountants, shell companies, and financial and consulting institutions. These criminal organizations use assets that make money laundering and increase complexity to finance money laundering in illegal money transfers between countries and terrorism. As a result, regulators have obliged financial institutions to implement various controls to prevent financial crimes. These are commonly referred to as "anti-money laundering obligations." Organizations that do not fulfill their AML obligations are punished with fines by regulatory bodies.

- size, The whole Africa Continent and the World Over

- philosophy.

Why the Need for Effective Leadership in Africa? To prevent susceptibility to criminal activities in the African Union Continental Free Trade Zone Area

T

his chapter looks at Leadership and the key Characteristics of Effective Leadership in African and the relevant of understanding the need for combating criminal activities, and improving Leaders positive interactions with citizens in the state. These include the development and demographic status of the African countries, and the dynamics of the African’s economy and trade. The chapter provides an overview of the African’s governance and democracy, and highlights salient features of its peace and security, or instability. Taken together, these characteristics will lessen the impact on the way criminality develops in the African Union Member States. Consequently, they are relevant for developing responses to criminality and illicit financial flows, and working to mitigate the impact of these factors on their economic development.

What is Leadership? Leadership in this context is a set of behaviors of African Leaders used to help people or Citizens of African States align their collective direction, to execute strategic plans, and to continually renew their States approach in Combating Financial Crime.

The typology of the Leadership we need in the African Continent

The political leaders of Africa come in all sizes, shapes, and persuasions. There are liberal democratic heads of state and heads of government, presidents and prime ministers; elected democratic leaders who become wily autocrats; strong authoritarians who brook no opposition and respect few freedoms; military men ruling because their followers are well-armed; kleptocrats who govern so that they can steal from the state and its citizens; a few who profess strong support for the public interest; and many who serve clan, family, and narrow conceptions of national “interest.” There are few women. Ideology plays little part in the very different styles and mechanisms of governance that these political leaders display. But nearly all of them are transactional; hardly anyone today is transformational in the manner of several of Africa’s founding fathers, such as Nelson Mandela.

All we need is African’s customary behavioral made leaders that align to the Need and Aspiration of our National Development. Africa has an oriented system of Love, dedication, and hard-work People that helps our upcoming generation thrive for the better and is careful for her People.

All leaders, to a certain degree, do the same thing. Whether you’re talking about a President, Head of States, an executive, manager, sports coach, or schoolteacher, leadership is about guiding and impacting outcomes, enabling groups of people to work together to accomplish what they couldn’t do working individually in a Nation. In this sense, leadership is something you do, not something you are. Some people in formal leadership positions of some African Countries are poor leaders, and, so many people exercising leadership have no formal authority but have good ideas. It is their actions, not their words that inspire trust and energy. What’s more, leadership is not something people are born with—it is a skill you can learn with the aim of developing. At the core are mindsets, which are expressed through observable behaviors, which then lead to measurable outcomes of how we handle our National issues.

Is there a Leader in Africa that is communicating effectively or engaging others by being a good listener? Focusing on their behaviors lets us be more objective when assessing leadership effectiveness. The key to unlocking shifts in behavior is focusing on their mindsets, becoming more conscious about our thoughts and beliefs, and showing up with integrity as their full authentic selves. There are many contexts and ways in which leadership in Africa exercised their Power. But, according to analyses of academic literature as well as a survey of nearly 200,000 people in 81 organizations all over the world, there are four types of behavior that account for 89 percent of leadership effectiveness:

· Being supportive to your People

· Operating with a strong results orientation for Development

· Seeking different perspectives towards development and Security

· Solving problems effectively Effective leaders know that what works in one situation will not necessarily work every time.

Leadership strategies in Africa must reflect each Country’s context and stage of evolution of their GDP’s and cause of depreciation symptoms and effect to National Development. One important lens is African’s health, a holistic set of factors that enable an African Countries to grow and succeed over time.

A situational approach enables leaders to focus on the behaviors that are most relevant as an African becomes healthier. Senior leaders must develop a broad range of skills to guide Africans. Ten timeless topics are important for leading nearly any African’s Nations, from attracting and retaining talent to making culture a competitive advantage. Leading African’s Nations: Ten Timeless Truths goes deep on each aspect. How is leadership evolving? In the past, leadership was called “management,” with an emphasis on providing technical expertise and direction. The context was the traditional industrial economy command-and-control Nations, where leaders focused exclusively on maximizing value for shareholders. In these Nations, leaders had three roles:

· Planners (who develop strategy, then translate that strategy into concrete steps),

· Directors (who assign responsibilities), or

· Controllers (who ensure people do what they’ve been assigned and plans are adhered to).

What are the limits of traditional management styles? Traditional management was revolutionary in its day and enormously effective in building large-scale global enterprises that have materially improved lives over the past 200 years. However, with the advent of the 21st century, this approach is reaching its limits. For one thing, this approach doesn’t guarantee happy or loyal Leaders or followers. Indeed, a large portion of Followers—56 percent—claim their Leaders are mildly or highly toxic, while 75 percent say dealing with their Larders is the most stressful part of their Nations troubles. For 21st-century African operating in today’s complex African’s business environment, a fundamentally new and more effective approach to leadership is emerging. Leaders today are beginning to focus on building agile, human-centered, and digitally enabled Africans able to thrive in today’s unprecedented environment and meet the needs of a broader range of stakeholders (Public and Private Sector, in addition to investors). What is the emerging new approach to leadership?

This new approach to leadership is sometimes described as “servant leadership.” While there has been some criticism of the nomenclature, the idea itself is simple: rather than being a manager directing and controlling people, a more effective approach is for leaders to be in service of the people they lead. The focus is on how leaders can make the lives of their Country’s Men easier— physically, cognitively, and emotionally. Research suggests this mentality can enhance both team performance and satisfaction. In this new approach, leaders practice empathy, compassion, vulnerability, gratitude, self-awareness, and self-care. They provide appreciation and support, creating psychological safety so their People are able to collaborate, innovate, and raise issues as appropriate. This includes celebrating achieving the small steps on the way to reaching big goals and enhancing people’s wellbeing through better human connections. These conditions have been shown to allow for a team’s best performance. More broadly, developing this new approach to leadership can be expressed as making five key shifts that include, build on, and extend beyond traditional approaches:

1. Beyond executive to visionary, shaping a clear purpose that resonates with and generates holistic impact for all stakeholders

2. Beyond planner to architect, reimagining industries and innovating business systems that are able to create new levels of value

3. Beyond director to catalyst, engaging people to collaborate in open, empowered networks

4. Beyond controller to coach, enabling the organization to constantly evolve through rapid learning, and enabling colleagues to build new mindsets, knowledge, and skills

5. Beyond boss to human, showing up as one’s whole, authentic self Together, these shifts can help a leader expand their repertoire and create a new level of value for an African’s stakeholders.

The last shift is the most important, as it is based on developing a new level of consciousness and awareness of our inner state. Leaders who look inward and take a journey of genuine self-discovery make profound shifts in themselves and their lives; this means they are better able to benefit their Countries. That involves developing “profile awareness” (a combination of a person’s habits of thought, emotions, hopes, and behavior in different circumstances) and “state awareness” (the recognition of what’s driving a person to take action). Combining individual, inward-looking work with outward-facing actions can help create lasting change. Leaders must learn to make these five shifts at three levels: transforming and evolving personal mindsets and behaviors; transforming teams to work in new ways; and transforming the broader organization by building new levels of agility, human-centeredness, and value creation into the entire enterprise’s design and culture.

What is the impact of this new approach to leadership in African?

This new approach to leadership is far more effective. While the dynamics are complex, countless studies show empirical links among effective leadership, Citizens satisfaction, investors’ loyalty, and profitability for the African Continent. How can leaders empower African’s Citizens? Empowering African State owned Agencies, surprisingly enough, might mean taking a more hands-on leadership approach. Countries whose leaders successfully empower others through coaching are nearly four times more likely to make swift, good decisions and outperform other African Countries. But this type of coaching isn’t always natural for those with a more controlling or autocratic style. Here are five tips to get started if you’re a leader looking to empower others: — Provide clear rules, for example, by providing guardrails for what success looks like and communicating who makes which decisions. Clarity and boundary structures like role remits and responsibilities help to contain any anxiety associated with work and help teams stay focused on their primary tasks.

— Establish clear roles, say, by assigning one person the authority to make certain decisions.

— Avoid being a complicit manager

· For instance, if you’ve delegated a decision to a team doesn’t step in and solve the problem for them.

Address culture and skills, for instance, by helping African State owned Agencies learn how to have difficult conversations.